Charting Power: How Maps Shape Political Narratives

The renaming of the Gulf of Mexico is a reminder that maps are tools of power. This visual reconstruction traces the Gulf’s shifting names, revealing how cartography legitimizes claims, shapes perceptions, and asserts dominance — from colonialism to digital geopolitics.

Laughed, Legislated, and Launched — A Joke Turned ’America First

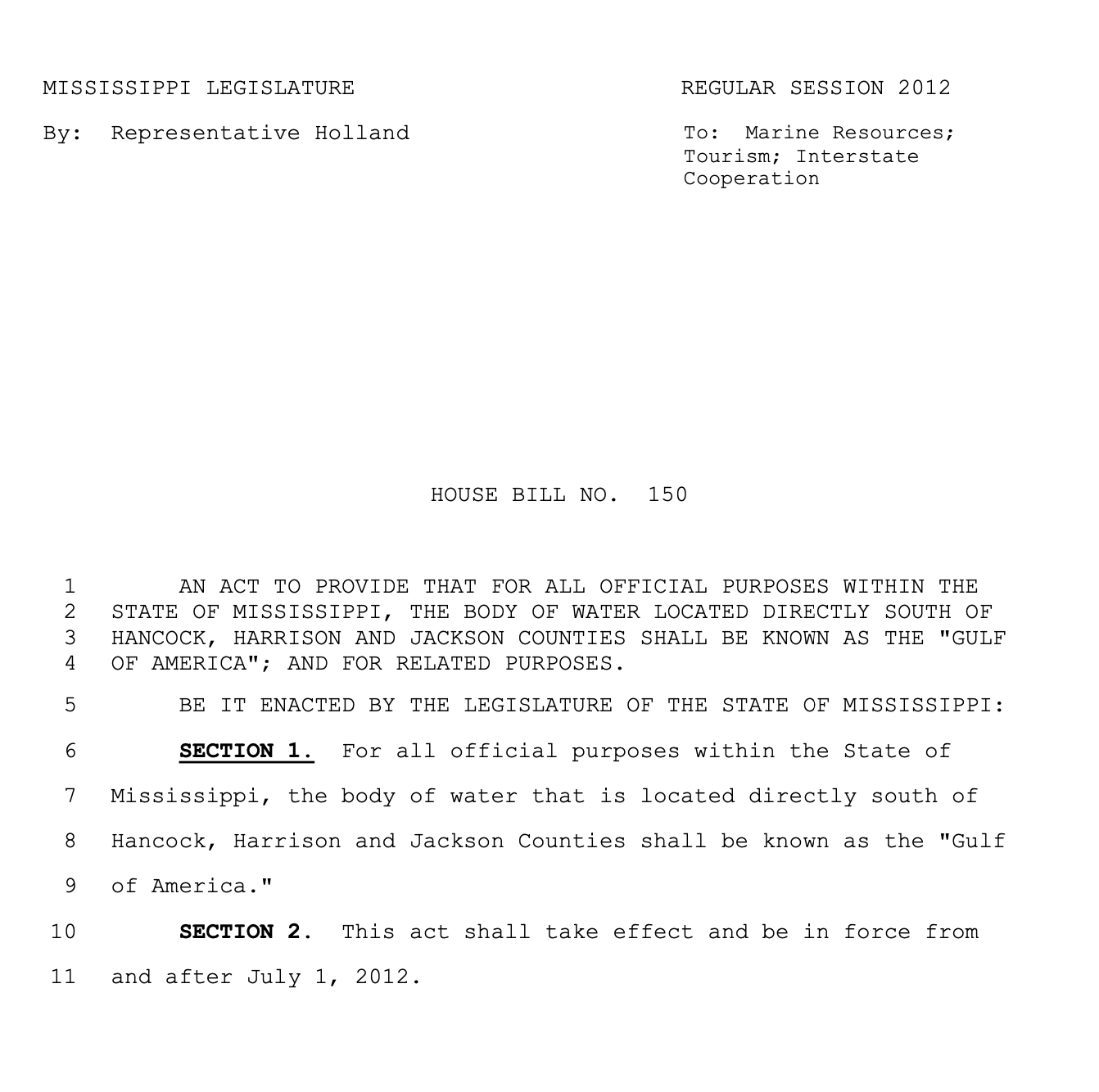

It was a mild, almost warm day in February 2012 when Steve Holland, a Democratic state representative from Mississippi, tried to make a joke. It is not delivered, if Holland slapped his thighs and burst into loud laughter; or if he was just wearing a silent, little smile on his lips. The one thing known for certain is, that Holland turned his special sense of humor into the House Bill Number 150 and directed it to the Marine Resources, Tourism, and Interstate Cooperation.

The bill — with the stoicism only a legislative decree set in the rigid strokes of a monospace font can convey — declared that

»the body of water located directly south of Hancock, Harrison, and Jackson Counties shall be known as the 'Gulf of America.'«.

It was set to take effect in July 2012.

Only, it never did.

Exactly one month and a day later, on March 6th 2012, the bill quietly died in committee. Before its demise, it caused quite a stir in the media. Holland later clarified that the bill was meant to be nothing more than a satirical jab at anti-immigration rhetoric which was a dominating political discourse at the time.

Thirteen years and three presidencies later the U.S. Interior Departement, under President Donald Trump, issued a note on its website regarding the »Restoration of Historic Names Honoring American Greatness«. Last updated on January 24, 2025, it states:

»In accordance with President Donald J. Trump’s recent executive order, the Department of the Interior is proud to announce the implementation of name restorations that honor the legacy of American greatness, […] , the Gulf of Mexico will now officially be known as the Gulf of America […]«.

Much like Bill 150, this executive order sparked —and continues to fuel— intense media attention. While many described the renaming as a political stunt and defended »Gulf of Mexico« as the rightful name, the irony is hard to ignore — this, too, is a name born from colonial history and hegemonic power.

Looking at the name of this specific body of water reveals a layered history, shaped by centuries of exploration, conquest, and geopolitical shifts. In reality, the story of this body of water —and the debates over what to call it— neither began with the Bill 150 nor is it likely to end with Trump’s recent decree.

Water with many Names — A Visual Reconstruction through World Maps

In seeking to piece together the changing names of the water body connecting the United States, Mexico, and the Caribbean, one is struck above all by the resounding (visual) silence before 1500. Long before European »contact«, Indigenous peoples such as the Aztecs and the Yucatec Maya navigated and most certainly also charted sections of the Gulf.

Their cartographical expertise is, for example, delivered in Columbus’s accounts of native offshore voyages and in Cortés’s remarks on the sophisticated cartographical practices (which he observed during or after his invasion). But because Indigenous maps were often produced on perishable materials, targeted for destruction by colonial officials or overwritten by the Spanish administrative cartography, only a scarce few survived in archives or through careful local safeguarding. An example of the prolific and beautiful mapmaking is shown below, however it does not depict the Gulf.

The Codex Quetzalecatzin

From an information design stand point this map is stunning: It shows a vibrant color palette, including the »Maya Blue«, a specific color generated through plant leaves and other materials. It information hierarchy uses a mix between a diagrammatical/pictorial representation (family lineage) and cartographical representation (an area which is now northeast of Mexico City). The Map also mixes latin writing systems with native language writing Systems.

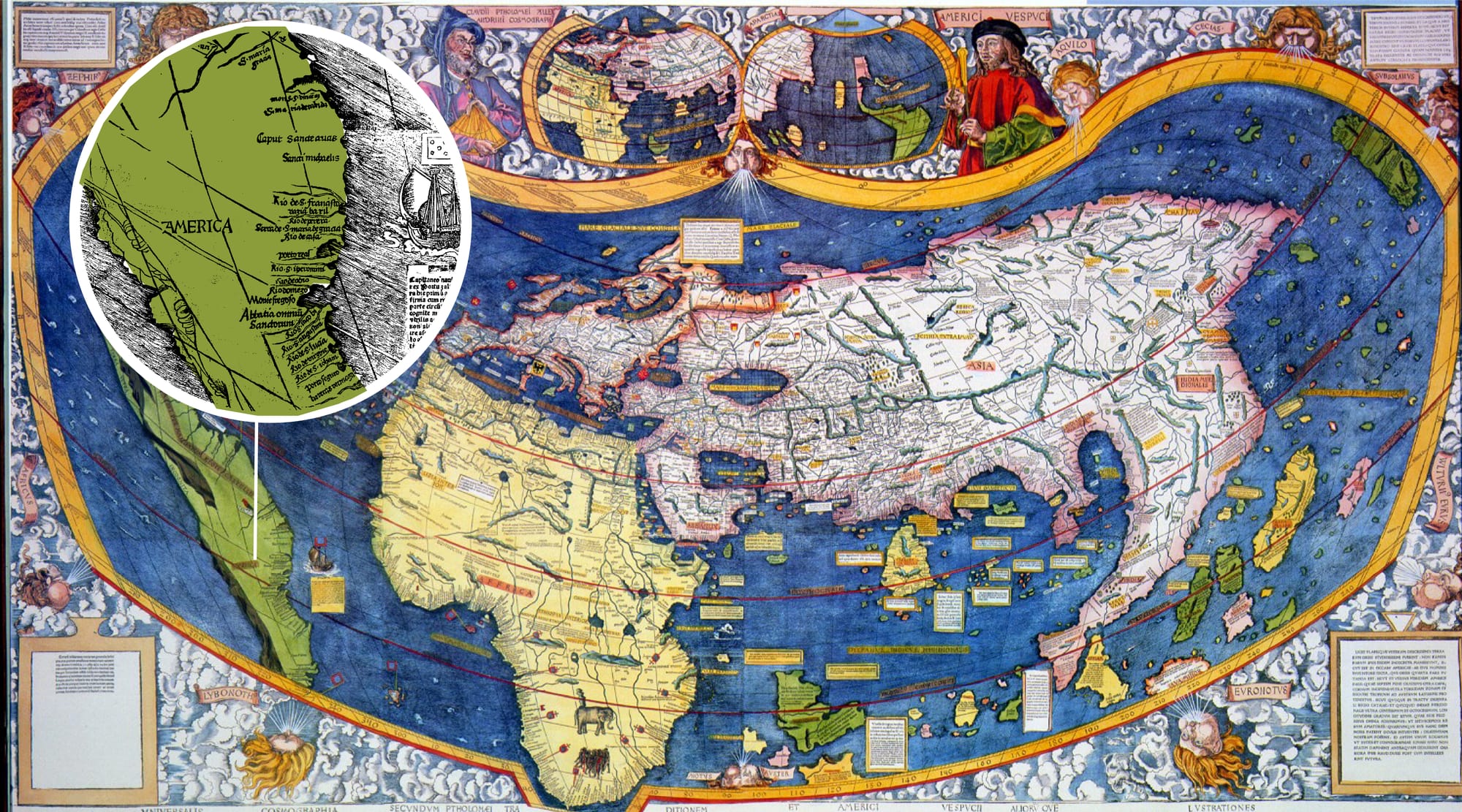

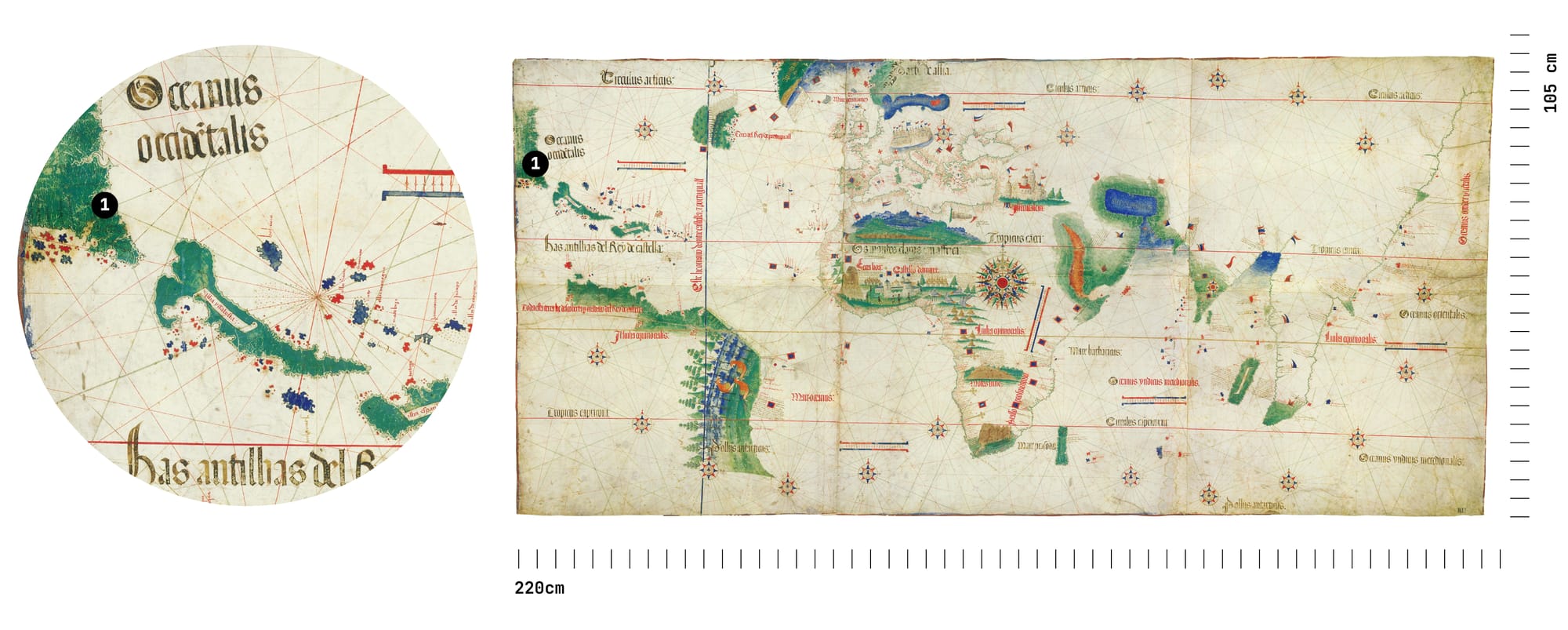

The very first world maps that charted the Gulf do not provide a name for this specific body of water. The Map of Juan de la Cosa dated 1500 is the first world map showing the Equator (No.2) and contained »Ground Truth« of the three voyages of Columbus (1492, 1493, and 1498), two voyages from Vespucci (1497 and 1498) and the first two voyages of Oabot (1497 and 1498).

The »New World« appears in color, predominantly green (No.3), while the »Old World« remains only outlined in contours (No.4), lacking the same visual prominence. This color distinction seems like a simple artistic choice, but might also reflect the European perspective of the time: the New World as both an enigma and a conquest in progress, an –yet– uncharted »opportunity«. The Gulf itself is only vaguely represented on the map, probably because of the limited understanding of the region’s geography at the time.

Another visual detail, almost hidden on the map, is the presence of flag-shaped symbols (a). These markers highlight a fundamental function of the visual tool cartography: asserting territorial control. In this case, these flag symbols represent claims over land and sea by emerging colonial empires. It illustrates how, throughout history, cartography was not only a means of representing geography but also a tool for reinforcing political authority and shaping territorial ambitions through visual representation.

This connection between mapping and power is also why, in this era, cartography was as much about secrecy and control as it was about discovery. Spain, for example, treated geographical information as a state secret, requiring ship captains to submit their reports or maps to the Crown upon their return. These documents were tightly controlled, classified, and deliberately kept out of the hands of rival European powers. As a result, many of the first maps of the »New World« were not published in Spain but in Italy, France, and Germany, often based on smuggled or second-hand data.

Two years after the publication of the Map Juan de la Cosa, in 1502, the Italian Agent Alberto Cantinoan smuggled the now called Cantino Planisphere out of Portugal for the Duke of Ferrara. The Cantino Planisphere was the first known map to depict the Gulf of Mexico with a recognizable shape (No.1) . However, also here the Gulf remained without a Name. (The Cantino Planisphere was also one of the earliest maps to show Portuguese claims in the Americas, reinforcing the political narratives established by the Treaty of Tordesillas (1494), which divided the newly discovered lands between Spain and Portugal. Unlike De la Cosa’s map, which reflected Spanish perspectives and priorities, the Cantino map served as evidence of Portugal’s reach and ambitions.)

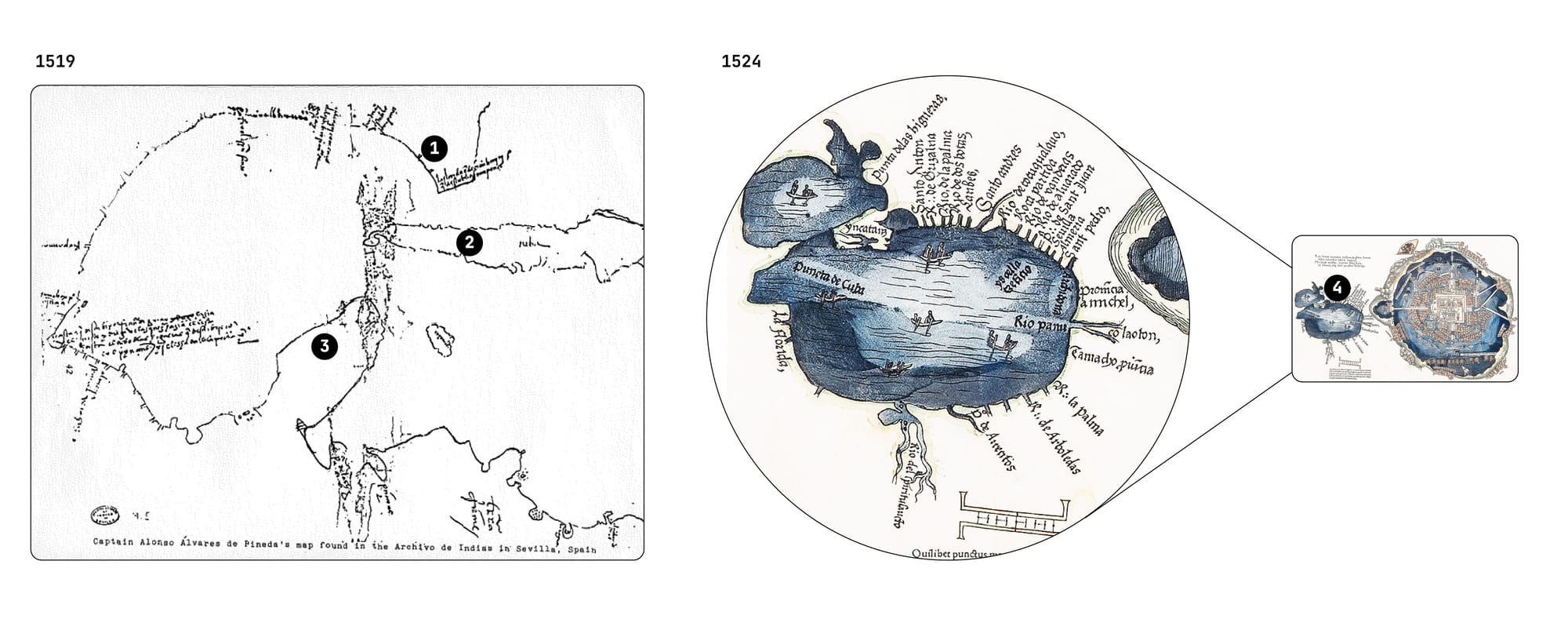

In the following years, regional maps show a growing geographical understanding of the Gulf of Mexico, with increasingly accurate depictions of its coastline. The Pineda Map (left) from 1519 and the First European Map of Tenochtitlan (right) from 1524 both with rich context that could fill entire volumes—far beyond the scope of this article. Yet, despite their significance, both maps notably leave the Gulf unnamed.

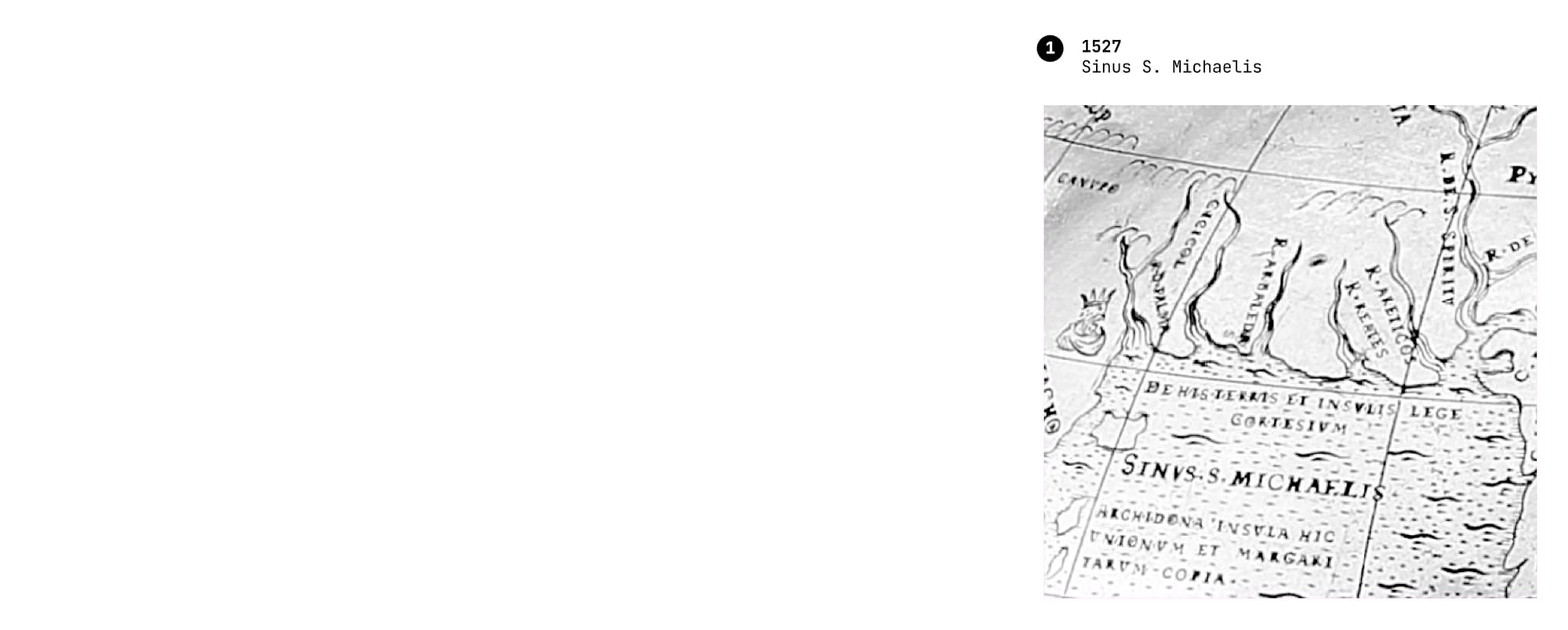

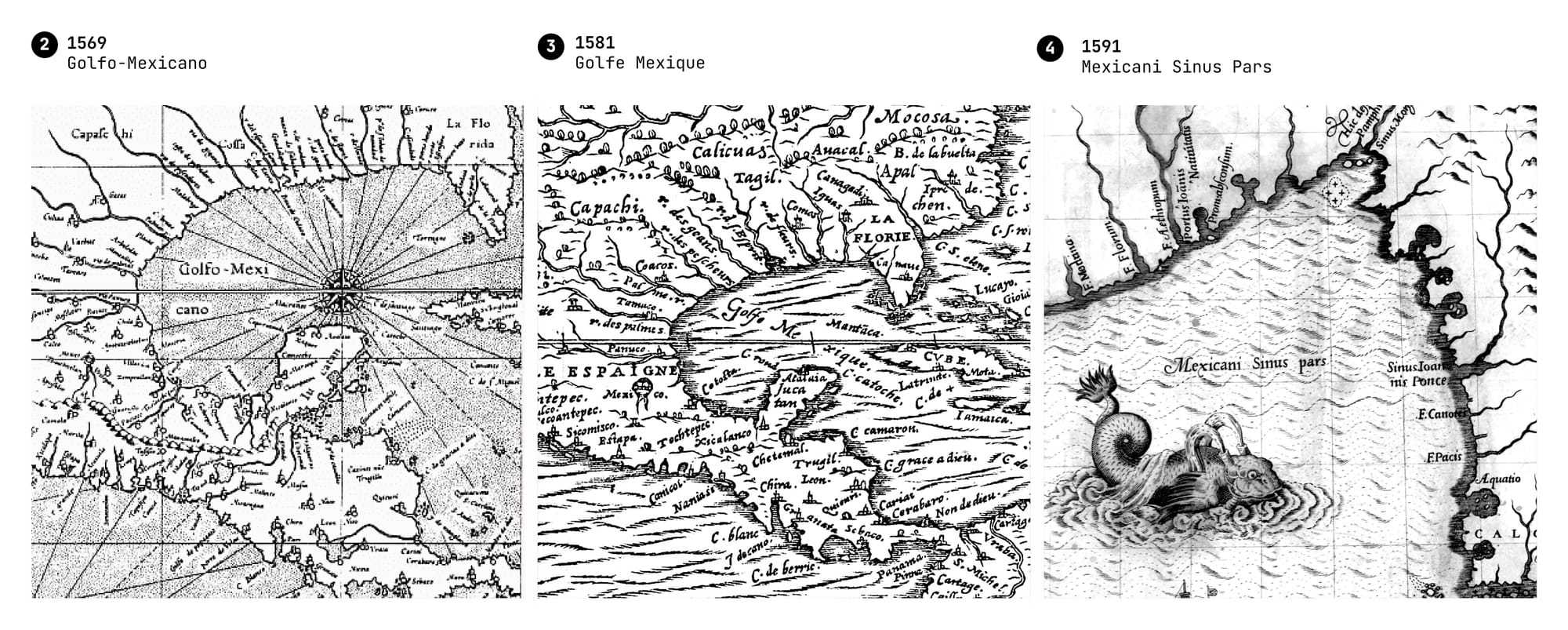

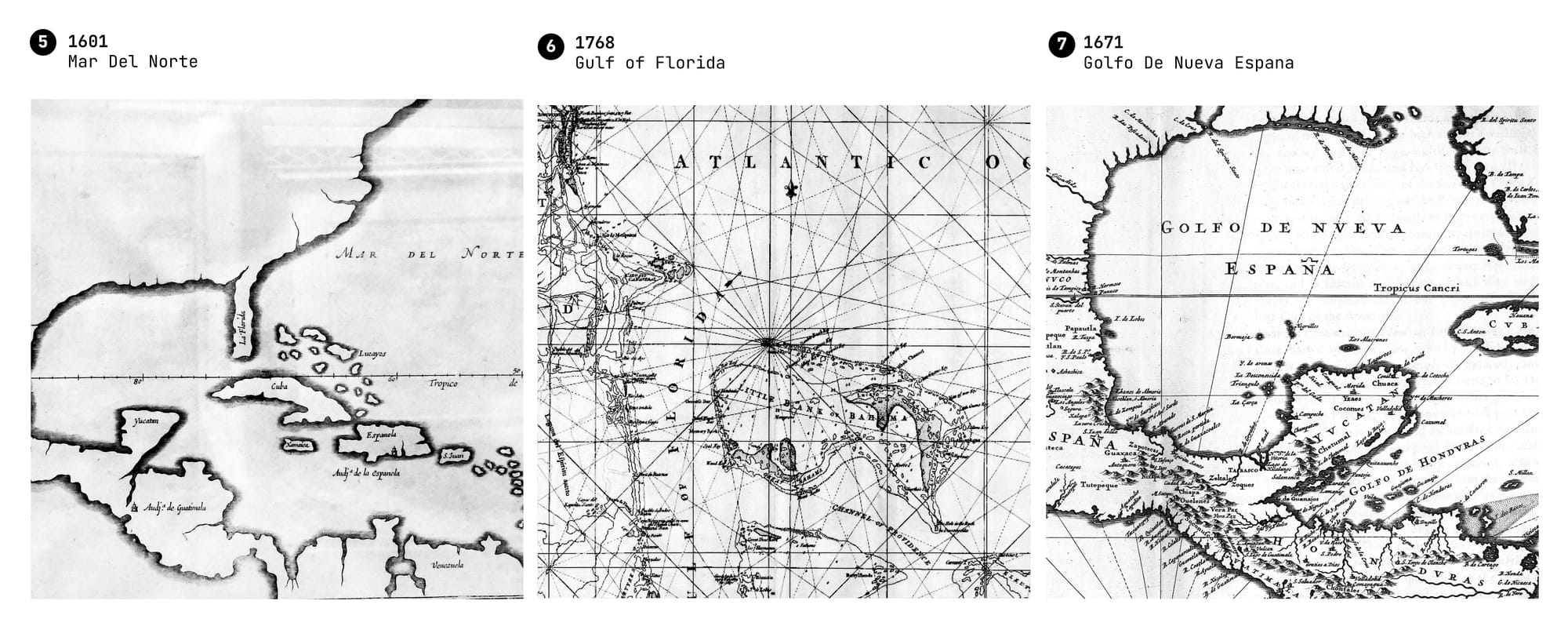

After 1527, over a span of 150 years, maps from various contexts bear witness to at least seven different names for the Gulf of Mexico. These include Sinus S. Michaelis (No.1), various versions of Golfo de México (Nos. 2–4), Mar del Norte (No.5), Gulf of Florida (No.6), and Golfo de Nueva España (No.7). And this is based solely on a visual reconstruction of maps in the public domain.

According to various sources, additional names existed as well. Before the arrival of colonial powers, the region was known as Nahá, meaning »Great Water«. Later, during Columbus’s voyages—when he mistakenly believed he had reached a seaway to Asia—it was even referred to as Mare Cathaynum (»Asian Sea«) in some European maps.

The World, According to Your Phone — Whose Map Are You Following?

As shown earlier, the names of places—whether cities, rivers, or entire water bodies—are not arbitrary. They are shaped by history, politics or cultural narratives. Each nation determines how it names places within its borders, but these choices have broader implications when maps are shared across international boundaries.

To manage geographical names on a global scale, the United Nations Group of Experts on Geographical Names (UNGEGN) was established in 1959. This working group, operating under the UN Economic and Social Council, is responsible for standardizing geographical names worldwide to facilitate international communication and reduce misunderstandings. The UNGEGN does not enforce naming conventions but rather promotes consistency and mutual recognition between countries. It provides a forum for national authorities to collaborate and resolve disputes over place names, particularly in contested regions.

However, national sovereignty remains the primary force in official place names. The U.S. Board on Geographic Names (BGN), for instance, standardizes names used in federal documents, just as other countries have their own naming authorities. When political leaders decide to change a name—such as Trump’s executive order renaming the Gulf of Mexico to the Gulf of America—these bodies determine whether and how such changes are reflected in official cartography.

But in an era where maps are no longer just printed, but implemented as real time digital interfaces, the question of who enforces naming conventions becomes even more complex.

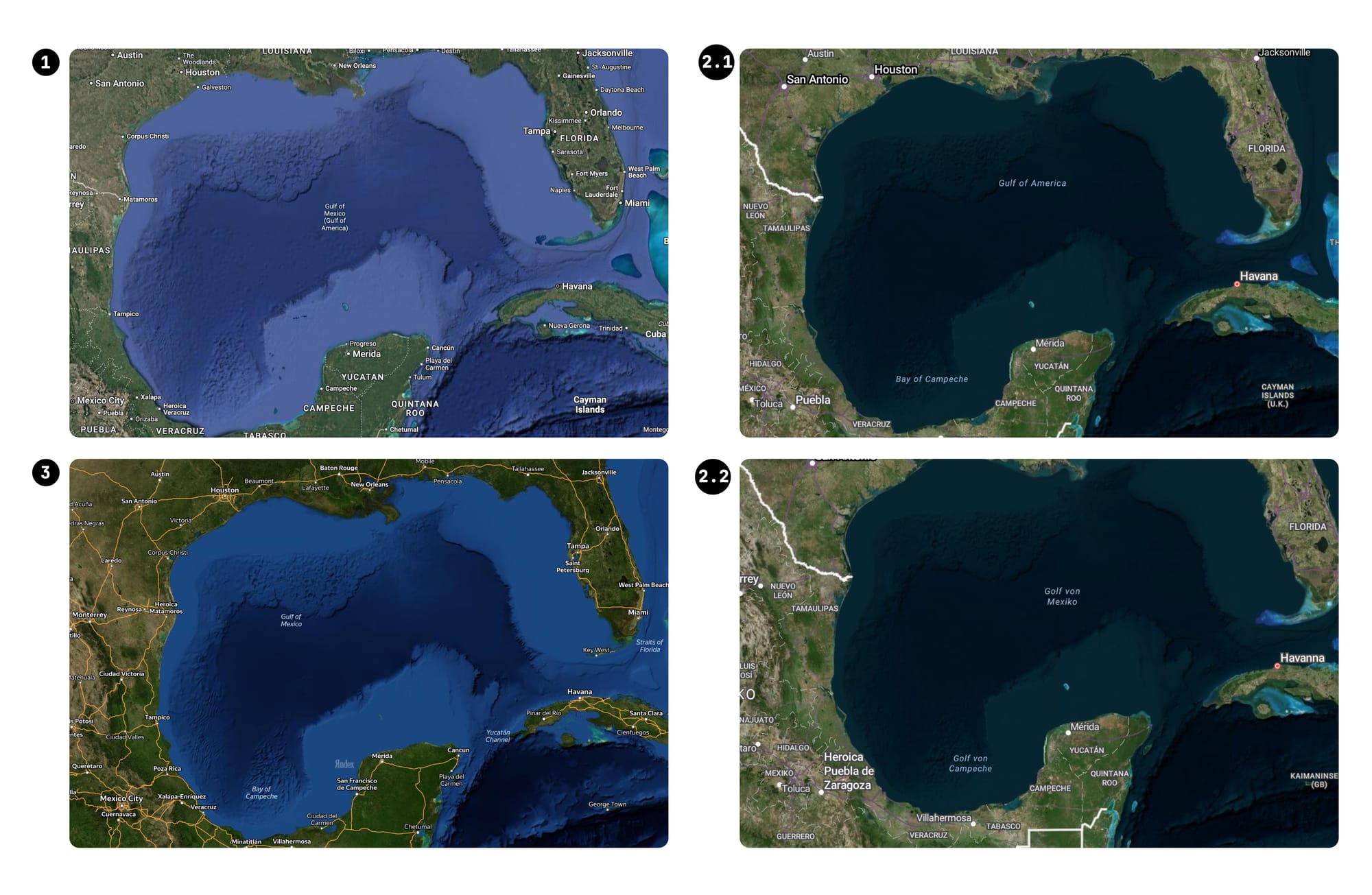

Global mapping services—whether Google Maps, Apple Maps, or OpenStreetMap—must decide whether to follow national directives, international conventions, or user-driven input. In response to President Trump's executive order renaming the Gulf of Mexico to the Gulf of America, various map providers have reacted differently. Google, according to a News Report, reclassified the United States as a »sensitive country,« similar to China and Russia, due to the geopolitical implications of the renaming. Consequently, Google Maps displays Gulf of America for users within the U.S., and both names for users elsewhere (No.1). Bing Maps have also updated their platforms to reflect the new designation using the same principle, but only showing the old Name for Users outside of the U.S. (No.2.1 & 2.2). Yandex Maps still shows the old name (No.3)

In contrast, OpenStreetMap, a collaborative mapping project, has experienced active discussions among its contributors regarding the name change. Some users have updated the map to reflect Gulf of America while others advocate retaining Gulf of Mexico leading to ongoing edits and debates within the community. The Forum counts until the date of this article publication 259 posts regarding this question.

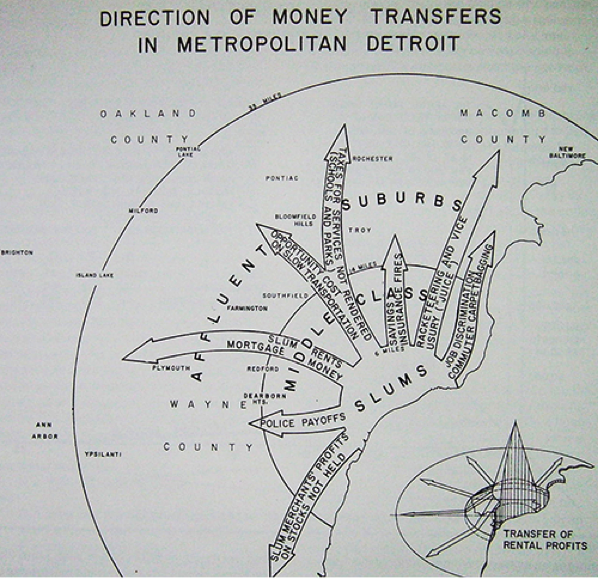

Visual Counter Measures — Counter Mapping, Critical Mapping, Radical Mapping …

This visual reconstruction of the Gulf’s evolving name reveals a larger picture: Maps are —as we have witnessed— no innocent tools of navigation, but of power, politics, and perception. Each renaming, each edit, and each omission tells a story about who controls the narrative and whose perspective is legitimized. Throughout history, maps have been wielded as instruments of dominance, from colonial expansion to modern-day geopolitical disputes.

— But what happens when the power to map shifts from hegemonic powers into the hands of open-source communities, activists, civil-society or other individuals? In my next newsletter, we will explore critical mapping, counter-mapping, and radical geography—where cartography is used not to reinforce dominant narratives, but to challenge them.

stay tuned and tell your friends.

The map is never just the territory.